>> from the library ofcongress in washington, dc. >> anne mclean: goodevening, i'm anne mclean from the library's music division. i'd like to welcome you to tonight'slecture by the culture critic and journalist, greil marcus,titled sam mcgee's railroad blues and other versions of the republic. this event is cosponsoredby the music division and the american folklife centerand we'd like to thank peggy bulger, nancy gross and toddharvey particularly.

we're delighted to be partneringtonight in presenting mr. marcus, a distinguished scholarof american popular music. he's admired for creativeexaminations and poetic associationslinking rock 'n roll to political and social theory. today the city paper described him as a unique culturalacademic rock critic and dylan scholar who'staught at princeton, berkeley and currently new york's new school.

many of you are probablyfamiliar with his books, including when that rough godgoes riding on van morrison, the old weird america, the shapeof things to come, mystery train, dead elvis, and lipstick traces and a remarkable dylan book youmight know like a rolling stone. i'm very glad to say thattonight he'll be signing copies of his newest book on bob dylan,which officially won't be released until monday, so that's kind ofnice, following tonight's lecture. please welcome greil marcus.

[ applause ] >> greil marcus: thank you anneand i thank anne and todd harvey, nancy gross for inviting me here,it's a great honor to be here and thank you all for coming. in 1964, a man named sammcgee made a new version of a tune he'd first recordedin 1934, railroad blues. and in the way that mcgee'sguitar seemed to have 20 strings and mcgee himself four hands,he was a whole orchestra. and the way that he shouted wahooas his notes rushed past and the way

that he aimed his voice at the skyhe was standing by himself on top of a mountain, alone inthe world, not another sign of human presence asfar as he could see. but whatever image came to mind as mcgee's railroad blues playedyou couldn't imagine the man who was singing standing still. as the tune played the singerwent from one place to another and he was no longermerely sam mcgee. from the first move into the tune

and almost unbearablydelicious downward swoop on a fact-based note making it feel as if you were beinglifted off your feet from that first gesturewhoever was singing and playing the song was somebodybigger, something more various than could ever becontained in an ordinary name. he was daniel boonewith faster feet. he was johnny appleseedwith songs instead of pips. he was cooper's leatherstocking with a sense of humor.

he was huck finn as an old manhaving long since understood as edmund wilson wrote in 1922, for what drama hissetting was the setting. the drama was to make asound that would prove to all the world the worldremained to be found even made. went to the depot, looked up on theboard mcgee sang for a first verse. taking a commonplace line andthrowing it away out of the way of the story that he wastelling on his guitar. went to the depot looked up on theboard, went to the depot looked

up on the board it said good timeshere, but better up the road. let's listen to sammcgee's railroad blues. [ music ] now whoever's playing in an instantyou can see them standing on a table in a bar full of drunksand then you can see him in a concert hall dashing back andforth from one side of the stage to the other as an audience of respectful folk revivalistssit thrilled and confused. you can glimpse a man walking intoa barbershop looking for change,

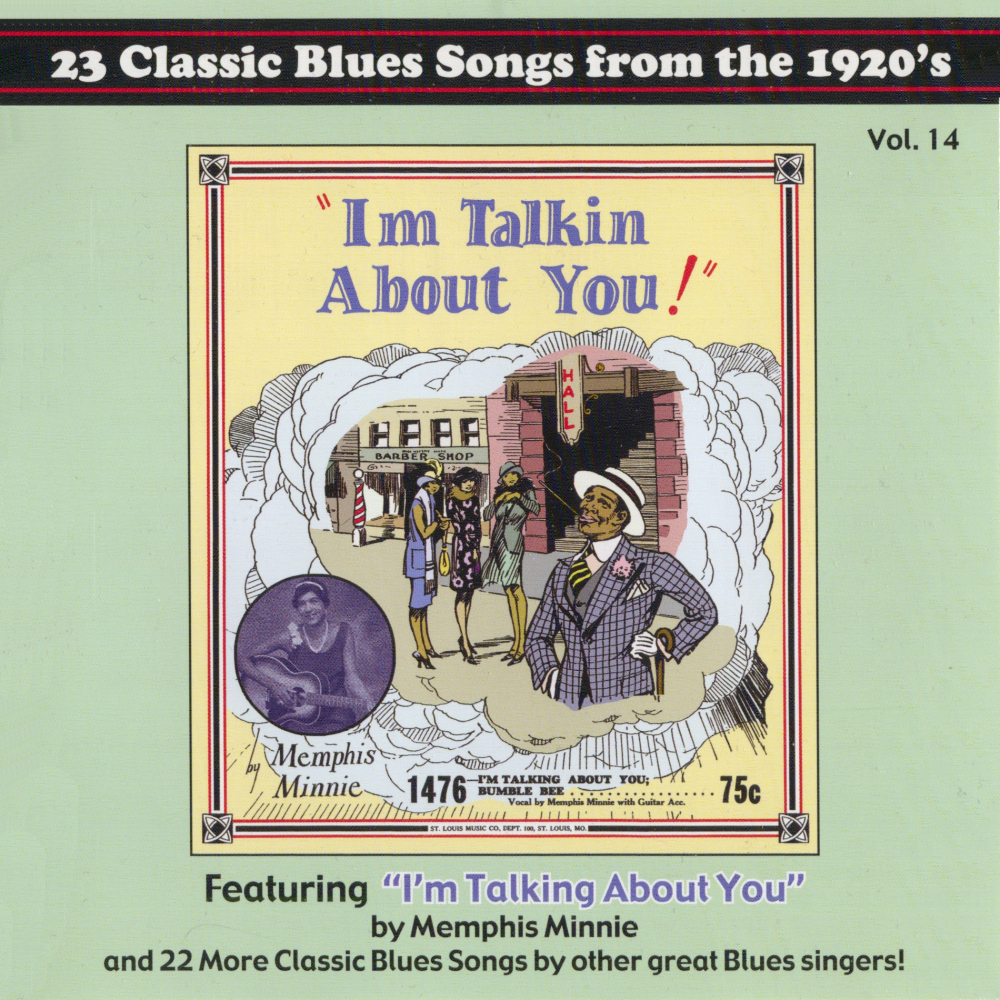

filling his hat and then tossingthe coins back at the rounders in the place like levonhelm and the band's up on cripple creek telling the taleof what his bessy did with her half of their racetrack winnings,tore it up and threw it in my face just for a laugh. who is this man? not sam mcgee, but the figurecomes to life as sam mcgee plays. he's one of many figures whoappear in american vernacular music as it was recorded inthe 1920's and 30's.

people who appear with such forceand such charm, such a broad smile or an implacable scowl is to claimthe whole of the country's story is if it was his or hers alone. it's incontestable forexample that there's no room for the creature runningthrough railroad blues in the nation established by belalam and his greene county singers as they recorded in richmond, virginia when okeh records helda joint recording session there in 1929.

a recording session that featuredas well the monarch jubilee quartet, the roanoke jug band, thetub size hawaiian orchestra, the bubbling over fiveand eight other acts. bela lam zanddervonbeliah lamb was born around 1870 and he died in 1944. he was a big man with ahuge handlebar mustache. and the greene county singerswere lamb, his wife rose, their son alva, rose's brother paul. in 1927 in new york they recorded aprofoundly peaceful version of see

that my grave is kept green, an old song about the countlessunmarked graves from the civil war that later found its way intoblind lemon jefferson's see that my grave is kept clean. in 1929 in richmond thoughthe sylvan glade was nowhere in evidence. bizarrely atonal banjo andguitar clang unpleasantly into even uglier singing. into nothing that can be calleda rhythm or even a melody,

but rather a translationinto music of a conviction so murderously complete,so uninterested in what you think you believethat suddenly you feel very small. on the outside of a story that'syours whether you want it or not, the story of jesus christ,your savior, come to take you and the person of thegreene county singers. and let's hear thegreene county singers. if tonight you'd end the worldis a sound of peopled rooted to their ground, certain

that no merely human forcecould move them an inch. it's a procession of singers, ofsingers stumbling down the street, stumbling because they can't keeptime because their harmonies are as arthritic as their hands must be. their cracked and quiveringvoices are any clue to their age. that the music builds on itselfuntil you too are waiting for the end of the world. if tonight should endthe world then what. they know you don't.

it isn't that the faithful and if tonight should end theworld would turn away from the man in railroad blues as a sinneror that they would turn him away from their church, they don'trecognize him, he doesn't exist. they're people who moveinto the settlement that the railroad bluesmanhas just left working hard, looking straight ahead, raisingtheir church, building the town so that when the man blowsback into the place in a year or so he won't even recognize it.

to the greene countysingers free in the embrace of the lord the man speaking inrailroad blues is no more a prisoner of his own animal -- isno more than a prisoner of his own animal appetitesand against people like him their towndoesn't even need a jail. bela lam's banjo picks out crown himlord above and you can feel that he and the rest of the greenecounty singers are already in another world, even as theyclaim all rights to this one. and in the same way it's hardto imagine the free american

in railroad blues countenancingthe destroyed individual in emry arthurs man ofconstant sorrow from 1928. it's not today an obscure song. bob dylan recorded a version ofit for his first album in 1962. and as the maid of constantsorrow judy collins sang it with pseudo elizabethan preciousnessat the height of the folk revival. the stanley brothersrecorded it, many more. in 2001, the cohenbrothers' film o brother where art thou george clooney,john turturro, tim blake nelson

and chris thomas king for amoment the soggy bottom boys with dan tyminski ofalison krauss's band, the voice be behind georgeclooney's dashing mic work. they swept the movie south withthis song and you didn't doubt for a minute that everyonethere wanted to hear it more than they wanted tohear anything else. let's listen to thissoggy bottom boys. that emry arthur who in 1929accompanied the virginia banjoist dock boggs on guitarwho boggs recalled him

and shot through the hands. he couldn't reach the cords,bullets went through his hands. he was the first person torecord man of constant sorrow. now you just say thefirst lines of the song. i am a man of constant sorrow,i've seen trouble all my days. those lines are instantlyoverwhelmingly sentimental and unless you completelyignore the lines as you sing as the soggy bottom boysdo and be going for speed and flash those lines areimpossible not to dramatize.

as bob dylan and judy collins found, the more quietly you sing thosewords the louder they become. and the more of a poseur, the moreof a fake they reveal you to be. but emry arthur bangs on his guitar as if he's been shotthrough the hands. you can almost seethe bone sticking out. plink, plink he says and hesays it no more musically than bela lam's band. i am a man of constantsorrow he says plainly,

as if he were sayingi'm hungry or i'm cold. as if he's learned to saysuch things with dignity. i have seen trouble all my days. it's that have, i haveseen trouble instead of the usual contractionof i've seen trouble. this says what the singer is sayingisn't obvious, it isn't common, it's not something youreally want to hear about. so this is emry arthur,man of constant sorrow. now you can imagine thegreene county singers trying

to pull emry arthur into their fold. they'd recognize him if only because they speak the same blanklanguage the greene county singers singing as if they don't care if youhear them even though their records and emry arthur's recordsthese weren't field recordings, these weren't taken down byfolklorists these were recorded for commercial record companies withthe idea that people would buy them. but the greene county singerssound as if they don't care if you hear them and emry arthursings as if he can't believe

that anyone would everlisten to him. but why would the man inrailroad blues even pause? in his thin voice whichimperceptibly moves from bitterness to acceptance from anger to peace. the fire in the man of constantsorrow offers a kind of challenge, a rebuke to god's gifts andit's this that will keep him out of bela lam's church. after a verse or two the tunlessnessof emry arthur's performance settles into a hurdy-gurdy beat and you'reno longer afraid of the singer.

he's put you at ease so hecan put you on the spot, so he can show you howabsolutely you will never know him. oh, you can bury mein some deep valley for many years there i will lay and when you're dreaming whileyou're sleeping while i am sleeping in the clay. it's the irreducibleindividualism of the details, details that rarely have ever movedinto other versions of the song, the already traditional song.

perhaps because theycommunicate as so specific to a particular individual that toappropriate would be a kind of theft that the folk processcouldn't even excuse. it's those details that sealedthe bottomless well of this song. the unusual reference to dreaming,the use of clay not just ground and the singer goes on afterthis verse not in death, but relating more of histravail, but he doesn't need to. like the greene county singers with if tonight should end theworld he's told a finished story

and having done so he's delivereda finished verdict in his words in my own true country theland that i have loved so well. if that nation as it's beencomposed into a republic of which the singer is acitizen has cast him out, then the country is afiction and there's no home for anyone or ought not to be. born in 1900 in wayne county, kentucky emry arthur diedin 1966 in indianapolis. and he likely wouldn'thave recognized

or maybe wouldn't have deignedto recognize the bob dylan who recorded man ofconstant sorrow in 1962, but he would've recognized avery old song, the very old song when first unto this countryas bob dylan sang it in 1997. whether he would haverecognized or accepted the majesty that dylan brought to a song asbereft as his own i have no idea. starting in the mid-1980'sdylan playing by himself with acoustic guitar andharmonica and then later with a band began working more

and more traditionalmaterial into his concerts. old songs about knights and damselsand sailors and buffalo scanners and all sung without a trace ofirony or doubt just an awareness of one's own smallness in the faceof the enormity of these figures. and many of these songswere collected on the insanely rigorousnine cd bootleg, the genuine never ending tour, thecovers collection 1988 to 2000, which presented dylan'sconcert performances of songs by others organized into differentdiscs for country and soul

and rhythm and blues and folk songsand traditional blues and pop right down to alternates and retakes. more versions of songs alreadyappearing on all the other discs. one last obviously redundantpiece of plastic meant to squeeze another $30 or soout of anyone crazy enough to even think aboutbuying this thing. but on this last disc,alternates and retakes, that's where the action was. the first eight cds make an enormouscolorless lump and in the last one

with every genre mixedup everything is alive. and here you find the version of when first unto thiscountry that sticks. when first unto thiscountry a stranger i came. you can't say more, you can'toverdramatize those lines, that's the whole storyof the country. as surely as a tv guidesummary of the film of moby dick i once saw wasthe whole story the country, a mad captain enlists others inhis quest to kill a white whale.

dylan takes all thedrama the song has. an electric guitar finds thehesitation in the melody, in the bass notes and it playsan actual overture and a wash of symbol noises like a wavelapping up the side of a ship and a muffled thump from the bassdrum lets you feel the singer step ashore. and then everything slows down as if before the storywas even begun you have to hear the ending and you do.

the theme has been stated andit's elegant and it's fine and it's beautiful in the waythat you can imagine the ruins of a greek temple are more beautiful than the actual completebuilding could ever have been. a second electric guitarturns the melody into a count and as the singer walks intoamerica his steps are measured and let's listen tothat for a moment. the singer courts nancy,her love i didn't obtain. for reasons that henever gives out of rage,

out of a will to self-destruction,out of a sense of irredeemable estrangementfrom the land and the people who already claim to belong. he steals a horse and he's capturedand his head is shaved, he's beaten, he's thrown into prisonand forgotten. i wish i'd never been a thiefhe says tearing the words out of his throat. it's so painful, you mightimagine the man finally free after five years, maybe 10 years,

but the pain in the man'svoice is its own prison. and so you can imagine him movingfrom town to town, bar to bar trying to find somebody to listen tohim, to listen to his story, to listen to his song andhe repeats the first lines of the song over and over again. and now with the finishedstory weighing down on every word the firstlines not just of the song, but the first lines of the country. now all these people, the happyman in railroad blues and the saved

in if tonight should save theworld, the dead man in man of constant sorrow andthe walking dead man in when first unto thiscountry they're all separates from each other. they're isolatos [phonetic] inmelville's words from moby dick. there's miles and milesbetween the church and this congregation of ishmaels. good times here, butbetter down the road the man in railroad blues sayswith every note.

neither the emry arthur in man ofconstant sorrow or the bob dylan in one first unto this countrywould hear that man anymore that bela lam wouldsuffer to listen to him. what these songs, what theseperformances say is playing. if this is a republicit's fated to scatter. it was made to guarantee itscitizens the freedom that was theirs by right not to limit it. everybody understandsthis and that's the rub. within the boundaries

of that freedom anything canhappen and everything will. if this is one republicnobody can see it whole and only the bravestand even think about it. now when sam mcgee firstrecorded railroad blues in 1934, he was just then stepping out of ahole that had opened up in the story of american vernacularmusic or folk music. hundreds of people had come forthto tell that story in the 1920's, when early in the decade it becameclear to northern record companies that they were payingaudiences for the kind of music

that these people already knew. stuff they could hear ona neighbor's front porch, in the barrel house for blues, forballads, for folk lyric hybrids of the two, for soundsthat carried novelty, for sounds that were alreadycalled old-time music. so from all over the south fromtexas, new orleans, the carolinas, tennessee, arkansas, alabama,mississippi and america that had hidden in folktalesand the unwritten journals of the wanderings the firstgeneration of african-americans

to be born out of slavery. this america emergedfrom the shadows of family memory andsolitary meditation. that america took the form of manybodies, profit, trickster, laborer, gambler, whore, preacher, thief,penitent, killer, dead woman, dead man, but the queerthing about this country was that this country was seenand heard almost exclusively by people who already lived in it. in other words, the records thatwere made were sent right back

down to where they camefrom and nowhere else. nowhere else with someexceptions that i'll get to. people bought records thatreminded them of themselves. that gave them proofof their existence. that raised their existencefrom the level of subsistence into a heaven of representation. and then came the depressionand the music market collapsed. communities that harboredthe stories, the nation at large still had notime for collapsed in its wake.

subsistence was no longera matter of the boredom of one day following another, oneindistinguishable following another. but it was a real drama andin this squalid tragedy, a father spending afamily's last dollar on a phonograph recordwould've been a horror story. so record companies recalled theirscouts, they cleared their catalogs and they closed theirrecording facilities. by 1934, when sam mcgee firstrecorded railroad blues businesses had begun to reorganize and notbecause the economy had come back

to life, but because people lookedout at the ruins of their society and they discovered with ashock that they weren't dead. when the recording of whiteand black folk music much of a traditional authorless andcommonplace, much of it composed, little of it copyrighted, mostof it entering the public domain as if it had been there forever. when the recording ofthis music began again, it was on a much more rational basisthan had happened in the 1920's. instead of the open auditions whereoddballs and families appeared

in their strange clothes withsears catalog instruments and their neighbors' or theirgrandparents' songs professionals were now favored. and instead of musicthat everybody knew and anybody could play recordcompanies looked for virtuosity, for music that only afew people could make. and this is where the firstrailroad blues comes from. born in 1894, sam mcgeelived until 1975 when he was killed ina tractor accident.

and he played and recorded for years with the great banjoist uncledave macon of the grand ole opry. sam mcgee could play anything andwhen he recorded railroad blues in 1934 he sounded as if he werein a cutting contest with himself. as if he were not onebut two guitarists. as if the two of them facing offagainst each other like duelists. and it's brilliant the way aninstrumental phrase goes up and down like a yo-yo and thenslips right back up. now you see it, now you don't.

but there's something missing,something only the version that mcgee recorded precisely30 years later reveals. the 1934 version of railroad bluesputs the spotlight on the performer, the fastest gunslinger in town. but by 1964, somethingcloser to what happened when vernacular music was recordedin the 20's was taking place. many of the people who madethat music were different from the people around them. they had more nerve, they were lessafraid of the shame of failure,

they had a deeper belief inthemselves, they took greater risks. the risk of appearing before abusinessman in a suit who more than likely would send you away as if you were no betterthan anybody else. the critic, robert christgauwrites tellingly about dock boggs. boggs passing an audition in hishometown of norton, virginia in 1927 and then traveling to new york torecord his scary and damn songs about death, but so full of beansat the chance that he's gotten that he can barely contain nothis rage, not his resentment,

not a sense of exclusion, hisfear of embarrassing himself in front of new york sharpies. what he can't contain is his joythat he's getting this chance. and you can hear the like ofthis all through the generic, but also unique discs thatharry smith compiled in 1952 for the anthology that at firsthe just called flatly american folk music. the thrill at the chance to speakeven only as a faraway premise to speak one's peace to the wholecountry, even the world at large

because the sears catalog not onlysold instruments it sold records by dock boggs, it sold recordsby sam mcgee in singapore, in tierra del fuego, inbarcelona, in japan, in turkey. the thrill to speak to the country. the thrill to imagine that you couldspeak to the whole world had to be at the root of the peculiar spellthat those records cast in 1952 for harry smith and all thosewho heard them and the same spell that those records cast now. when in the 60's folkrevivalists sat before

such 1920's and 1930's heroes. as mississippi john hurt, clarenceashley, dock boggs, [inaudible], skip james, [inaudible] housethey might've celebrated them as representatives ofthe people, of the folk, as the folk musicians of the folk. but as they listenedand as they watched, as they were thrilled theymay have been responding less to what made thesemusicians part of the folk than what set themapart from the folk.

their ambition, their innerdrive, their inability to tolerate their fellowhuman beings. but the music is nothing if not amystery and the mystery that occurs when a version of the nation'sstory that has been excluded from the story as it'sofficially told is suddenly offered to the public. that's what happened in the 1920's when southern musiciansproduced their version of america and taken together they arguedfor a more contingent life,

a less absolute death, an americawhere nothing was impossible and no settlement was ever final. and in this mystery the radicalindividualism that you can hear in 20's folk musicis always questioned and it's questionedby the same voice. one of the most shadowyfeatures of the music, one of the most queer isthe element of anonymity. the way the performer seems to stepback from himself or herself back into the community of whichthe performer is a part

or if the performer is not partof a community or sounded as if he or she couldn't be the anonymityof the way the performer seemed to slip back into the oblivionwhere he or she lived alone. like paul muni stepping back from acamera and into darkness at the end of i was a fugitivefrom a chain gang. how do you live he'sasked, i steal he says. when the tension between theself-presentation of the artist and the anonymous, even seeminglybodiless being behind the artist comes into a verge the resultis something no less exciting

and no less unsettlingthan the appearance of the radical individual. and this is what ithink is happening in sam mcgee's railroad bluesas he recorded it in 1964. this is no longer theexperienced side man stepping out to claim his own career,to record under his own name, to show off all thetricks in his bag. something bigger is happening andin a country with more room in it than the country presentin the 1934 version,

a country with more roomin it comes into view. and you're hearing someone who'sseen all over the country its past, its future and he's madea remarkable discovery. america has never changedand it never will. in a version of the republicthat's enacted in railroad blues in 1964 nothing mattersbut movement. how you move, how you carryyourself, the promises you make in your very demeanor, the wayyou walk, the way you talk, the way your clothes fit, the wayyour expression fits your face,

the way your face somehowchanges everything you see. the specter in the musicemerges immediately, the pioneer, the wanderer and in hisfreedom he threatens those who stay home working,saving, hoping, frightened. but he also leaves a blessing without living his life you'reallowed to know how it feels. so it's no longer sam mcgee,but a kind of abstraction who offers railroad blues in1964 or in 2002, 27 years later on a smithsonian folkways collectioncalled classic mountain songs,

which is where i firstheard railroad blues. when mcgee recorded in 1934that signpost that appears in the beginning of the song wascrucial, the kickoff to the record. went to the depot looked up onthe board, it said good times here but better down the road. in 1934 that was a directand political statement. it had to be said in1934 in the ditch of the depression it was the lastthing anybody could take for granted if they could believe it all,

better times down theroad, good times here. and the same words are saidin 1964, they're tossed off. but as an event in the musicthey've already happened, you've already heard it,you've already felt it. that swoop, that astonishinglift, that fat note breaking into a thousand glittering fragments as the strings shake have alreadycalled the train before the man gets a word out of his mouth. those high notes are no longera performer's calling card,

they have a life of their own. those notes are thinnerwith every measure. the way the note stretches outall the way out you can't believe that it's still hanging in the air. and the way a following note seemsto just barely draw the breath of that first note andthen continue the story. the bass note that says notso fast, the notes shoot out of the air they don'tpay any attention to it. you're sure they're goneand then they pick up again.

that's what's uncanny, the sense that in the truest talesthe country can tell about itself those talesmust be incomplete just like that note stretchingout, stretching out and never coming to an end. those notes, the countrystory has to hang in the air so that anybody can find it, so thatanybody can take it out of the air. and that finally is what took placeat the beginning of this story, a story about a certainhistorical emergence

of certain versionsof the american story. now there's one piece of musicthat i know that sees every gothic, pious, drunken, murdering,thieving loving figure moving through the old americanmusic for who he or she is and embraces them all and songis richard rabbit brown's james alley blues. it was recorded one day in 1927, the only day that richardbrown ever recorded. and for me that he recorded onlyonce is like melville not bothering

to keep hawthorne'sletter about moby dick, the letter of which melvillecould say i spent a sense of unspeakable security isin me because hawthorne had in melville's unbearably directwords understood the book. we'll never know whathawthorne said. the smallest, most modest notescreep out of brown's guitar like tadpoles swimming in searchof their melody, their rhythm and a bass note gongsshaking the air. nothing is pressed, anold ragged voice sour,

laughing at its own sourness beginsto tell a story about a marriage. and he snaps at his strings to drivea point home, but every time he does that a weird gonging is therepulling the real story away from the story that being told. pulling the story awayputting it in the air. this is james alley blues. when jerry leiber and mike stollerproduce the drifters' there goes my baby in 1959, the first timeanybody ever layered the equivalent of a complete symphony orchestraover a piece of rock 'n roll.

the effect they said waslike a radio dial caught between two different stations. you can imagine that rabbit brown'sjames alley blues could've had a similar effect on those few whoheard it except it would've been as if the performer existed betweendifferent eras, different lives, different ways of understandingthe world and like there goes my baby madeyou understand that the divisions between those thingsare meaningless. that was the meaning

of that mystical gongingbehind the prosaic facts that the singer was relating. that was the meaning of the smallsearching notes that shot out ahead of everything blindlyseeking a destination that could never be named. it was those same tiny seekingnotes that sam mcgee would seek out himself in 1964 -- 1934,but not truly recapture until three decades after that. he would from the startcast off the fatalism

that rabbit brown's notescarried, the thick fat notes that mcgee would use tosymbolize escape and liberation. that swoop, that up and down, that if you don't believe i'mleaving you can count the days i'm gone. notes that in jamesalley blues are filled up by brown's echoingflapping gongings not warnings of what might happen, butportends of what will happen. in mcgee's hands those noteswill no longer speak of death.

and if tonight should end theworld, man of constant sorrow and when first unto thiscountry the singers value nothing so much as death. and james alley blueshas room for them too. the small notes in james alleyblues move like mice scurrying from one room to anotherand never stopping and the house only getsbigger as they move. the man singing james alley bluesand you have to imagine him small and wiry and weary moving carefully,smiling, looking over his shoulder.

the man singing james alleyblues welcomes them all and they enter his house becausethey sense that he knows more about death than they do. but that's not allrabbit brown knows. railroad blues is frank about thefact that it's made for pleasure. it's an argument that freedomis more pleasurable than death. if tonight should end theworld, man of constant sorrow and when first unto thiscountry are arguments that death is moremeaningful than pleasure.

arguments that hide their power andpassion or their perfection of form, elements of performancethat give pleasure because their beauty makes it seemas if their arguments are true. but rabbit brown knowssomething about pleasure that it seems nobody else does. he knows how to give pleasure as if it were the giftof a guardian angel. and what he leaves behindthe sense of a place so big that there's room for anyone.

a place that's too big for anyoneto escape is exactly a story that can only start in themiddle with whoever telling it like sam mcgee in themiddle of railroad blues, rabbit brown in themiddle of james alley blue, with whoever tellingthe story unsure if he should go forwardor if he should go back. thank you. i have to ask somebodywhat time it is. [ inaudible comment ]

anybody has any questions,any arguments, disputes i'd be happyto try and respond. >> hi, i was interestedin interested in hearing the dylan versionof when first unto this country which i've never heardpartly because what i hear in that jangling electric guitar atthe beginning of it is an imitation of the autoharp of the new lost cityramblers who recorded that song. and we have a fieldrecording here at the library, which i believe was the source ofthe new lost city ramblers version

and i'm just wondering if thosesort of specific histories of individual songs andperformances touch on the sort of more general historicalcontext of these songs that you're talking about. >> greil marcus: yeah, imean threads of scholarship, the kind of knowledge thatyou're talking about move all through this story, but secretly. bob dylan's knowledge of thekind of music that i was talking about tonight is enormous.

and i mean knowledge of who recordedwhen and in what city and who was that person recording with and who was the engineerthat kind of knowledge. and so what you've justsaid there's no way that he didn't know the newlost city ramblers' version and it's very, very likely that he knows the otherversion you're talking about too and that all that goes in there. and it's a way of keeping thestory going and passing the baton

from one person to another,but also changing it. because there is a different --because yes the autoharp melody and even the orchestration isthere in that guitar opening and yet there's a different kind ofdrama, there's more glamour to it, there's more cinematic suspense,you know, it's in color. at least that's how i hear it. but you're completely right thatthat's all present and, you know, it's present all through. none of these people who i wastalking about tonight were ignorant

of what anybody else wasdoing, they were all listening, they're all in competition, they'reall stealing from each other. >> you kind of the at the end youfinished with the rabbit brown or all the fellows the storythat had to start in the middle and the speaker didn't know, thesinger didn't know if they should be or head back or heading forward. so i wonder if you think rabbitbrown knew just how powerful he was when he was recording that songand the meaning that he was getting out of it or is that something

that comes later once theaudience gets to hear it. >> greil marcus: well look here'sa guy he's a new orleans street singer, he really supportedhimself by standing around lake pontchartrain andoffering to serenade couples when they would take a boatout on lake pontchartrain. and can you imagine, youknow, you're about to propose to someone you think it wouldbe really romantic to go out on the lake and wow,we'll get this guy to sing and he'll sing something reallylovely and create the mood

and he sings james alley blues. so here's this person and hegets once chance to record and nobody knows exactly when hewas born, he died i think in 1935. and he gets one chance to record and he can probably figure he'snever going to get another chance, you know, maybe somebody toldthe record scout you ought to hear this guy or maybe somebodywas hanging around the lake and heard him gives him achance to record for victor, you know, for a major company.

and this is his chance,this is his one chance. he records five songs that day. and this is his song, this isthe one he's really worked on, this is the one he's craftedout of pieces of other old songs that he's put togetherin his own way. that he's worked out an arrangementfor and he knows this is a chance to get it right, he's nevergoing to get another chance. i think it's the greatestrecord ever made and i don't say that as any kind of joke.

from the time i first heardit i thought this must be. that was let's seethat was 40 years ago and i haven't heard anythingbetter yet, so maybe so. yeah, yeah. and so one of other recording hemade of the five was a version of the titanic and it's a version of the titanic unlikeany i've ever heard. the words are completelyconventional, the way he dramatizes them is not.

you know, he says you knowand this was happening and oh my god can you believethis and have you heard. but this is a version of the titanictakes into itself the knowledge that everybody in theafrican-american community knew. that the titanic advertiseditself not only is unsinkable, which is what's come downto us, but as all white. not only were there no blackpeople allowed as passengers, not only were there no black peopleemployed as stewards or waiters in the dining rooms they weren'teven going to have black people

in the boiler roombeneath the hold, nowhere. but there was one black person whostowed away on that ship according to many versions of the song and iwon't go into what happens with him. the way rabbit brown sings thesong the titanic when he gets into nearer my god, then theway he stretches out the line. he sings these lines with somuch glee, with so much delight at all these people goingdown, it's really something. but it's not like this, it'snot like this perfect record with these sounds unlikeanybody had ever made.

well i could go on as you can tell. >> what happened tothe black stowaway? >> greil marcus: excuse me? >> what happened to the blackstowaway of the titanic? >> greil marcus: well he wasthe guy who got into a lifeboat and he was sitting in thatlifeboat and he was looking up at all the women onthe ship who began pulling up their dresses saying take me,take me i'll give you anything and he just turned hisback and went away.

he was known as shine in song. yeah. >> i'm interested in thisquestion or this statement you made that the lobby singers wereinvested with this kind of radical individualism. and if i heard you right, you said if this is this a republicthat's made to scatter. and that is so different thanthe folk music revival that was so invested in this sort ofsocial collective and this idea

of a republic, a differentkind of republic that was based on thosekind of ideals. so i wonder if you could speaka little bit about the tensions that were there between thesepeople that were coming to perform at these folk festivals in newport and whatnot they were considered thefolk by the folk movement revival, but perhaps were coming with as yousay different ambitions and whatnot. >> greil marcus: well, i meanit's a question of ideology and it's a question ofideas that people bring

to an event before they'veexperienced the event. an idea of somebody's identity that you already form beforeyou've ever met that person. and, you know, mike bloomfielddescribed this maybe better than anybody. he said, man's lips had playedelectric guitar for years in texas, but when the people from thenewport folk festival brought him up they made him leave hiselectric guitar behind. he said they treated himas if he was the tar baby,

meaning just a figure fromblack folklore not a real person who could make his own decisionsabout how we wanted to play and how he wanted to sound. he had to be brought forth asa representative of the folk and the folk didn'tplay no electric guitar. that's the best way ican answer it briefly. >> so were there anytensions there [inaudible]? >> greil marcus: yeah, i meanthere was tremendous tension. i mean you take somebodylike clarence ashley,

somebody like skip james who wereordinary disagreeable proud people and they were, you know, put inyo9u know kind of musical forums where the whole point wouldbe to illustrate a genre. and these people would say i'm not agenre, you know, this is what i have to say, this is my way of saying it. and, you know, there wouldbe a lot of anger there and sometimes it would comeout and sometimes it wouldn't. and often it would come outthough in the performances that you saw that one could see.

someone's going to have totell me when i have to leave. >> [inaudible] one more question. >> greil marcus: okay. >> [inaudible] inviteeverybody to the book signing. >> greil marcus: ifthere is one more? i didn't mean to be intimidating. >> anne mclean: well thankyou very much all for coming. >> greil marcus: thank you. >> anne mclean: greilmarcus very, very much.

>> greil marcus: thankyou for coming. >> this has been apresentation of the library of congress, visit us at loc.gov.

0 Comment

Write markup in comments